Welcome to our homepage for the International Agroecology Exchange – Reflections from the US Delegation to South Africa

2017 South Africa-US Agroecology Exchange

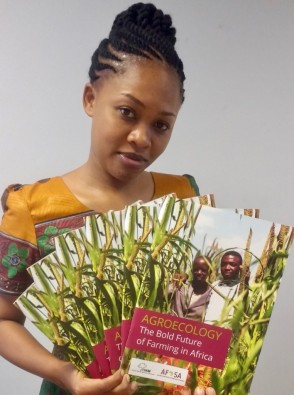

In October 2017, seven delegates from the US representing farmworker and African-American farmer organizations participated in the second South Africa-US Agroecology Exchange. For 10 days, the delegates visited the provinces of Gauteng, Limpopo, and the Western Cape to meet with small farmers, farmworkers, Agroecologists, and organizers in the Food Sovereignty movement. Together they learned and exchanged social, political, and technical aspects of Agroecology. The 2017 Agroecology Exchange was co-organized by US Food Sovereignty Alliance members WhyHunger (NY), Community Alliance for Global Justice (WA), and Farmworker Association of Florida, and South Africa-based Surplus Peoples Project. (Please read this press release for more background and see photos from the Exchange.)

Article Series

Starting in November and ending in January, members of the delegation will author a series of articles reflecting on different aspects of the Exchange. They will share how their trip to South Africa shaped new ideas, tactics, connections, and other means of continued engagement in the global Food Sovereignty movement, and how they’re bringing these insights to their local organizing.

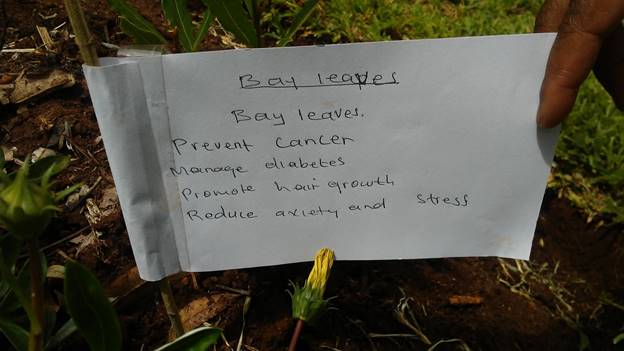

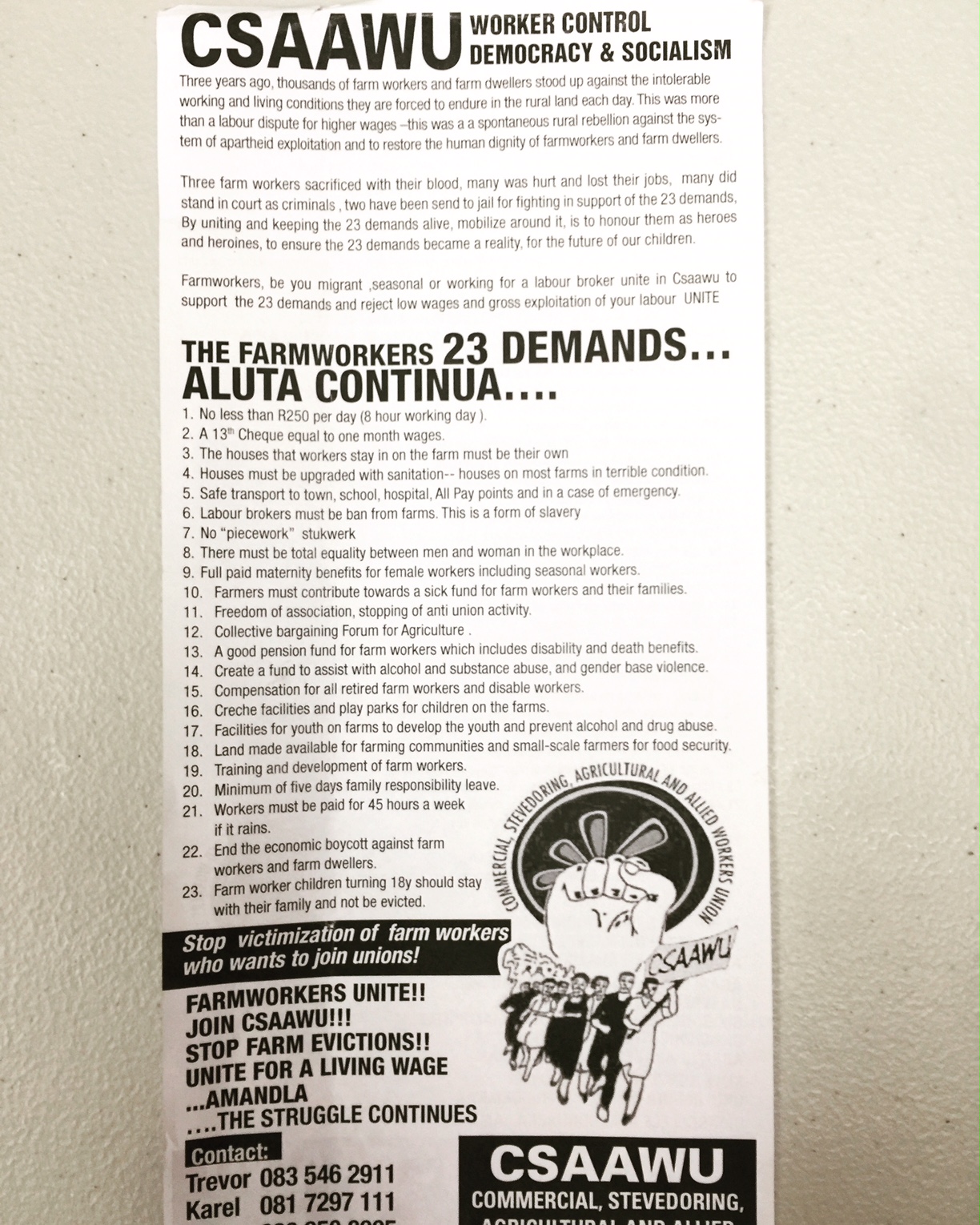

The series will also include perspectives on Agroecology in South Africa after learning from on-the-ground practitioners involved in organizations including Surplus Peoples Project, Mopani Farmers Association, African Centre for Biodiversity, Ithemba Farmers Association, the Commercial, Stevedoring, Agricultural and Allied Workers Union, Mawubuye, Trust for Community Organization and Education, Rural Legal Centre, and others.

Article Series November 2017 through January 2018

Update: Links to published articles:

- Restoring my Indigeneity: Reflections on South Africa Agroecology Exchange by a Queer Black Urban Farmer By Dean Jackson, Executive Director of Hilltop Urban Gardens in Tacoma, Washington

- Farmworkers Resist and Organize: Connected Struggles for Farmworker Justice in South Africa and the US By Edgar Franks, Organizer with Community to Community Development in Bellingham, WA

- Thoughts on Intimacy with Food, Land, and Women from South Africa: “Where there are women you can never go wrong.” By Alsie Parks, Field Organizer for Southeastern African American Farmers Organic Network (SAAFON)

- Justina’s Reflections on the US-South Africa Agroecology Exchange By Justina Ramirez, Community Leader with Farmworker Association of Florida

- En La Lucha No Hay Fronteras, In The Struggle There Are No Borders By Kathia Ramirez, Organizer, CATA (Comite de Apoyo a los Trabajadores Agricolas/ The Farmworkers’ Support Committee)

- Farming with Influence By Shalon Jones, Mississippi Association of Cooperatives

Please help distribute these necessary analyses on the importance of Agroecological Farming!

Agroecology is an agricultural method based on the traditional knowledge of those who cultivate the land. Its practice is critical to addressing hunger, cooling the planet, and increasing communities’ access to basic resources such as land, water, and seeds. The increased corporatization of agriculture in Africa and the US sidelines small-and-medium sized family farmers in service to increased profits for agribusiness. The South Africa-US Agroecology Exchanges exists to directly confront this trend and to exchange experiences, tools, and strategies for resistance and to strengthen the Food Sovereignty movement.